I can't explain it, my long absence from this blog thing. Recent months have seen an uptick in comic book consumption, but that's no excuse. The truth is, like so many Twenty-First Century middle class Americans, I have trouble balancing the demands of work, primetime television, literature, kid-oriented action cartoons, comic books, coffee consumption, bills, and blogging. I'm told that interpersonal interactions can also be very taxing, which is why I stay away, doncha know.

Anyhow, presented here in no particular order is a brief summation of what all I read since, damn, June:

V., Thomas Pynchon. This was a re-read; I was trying to get a friend to read along with me. Every time I revisit Pynchon, it's a reaffirmation of why I say I like him so much. Between readings, I figure it's just that I'm an obnoxious jackass, but it turns out he's really fucking fun to read. This reading was accompanied by J. Kerry Grant's A Companion to V., which was no Ulysses Annotated, but pretty worthwhile all the same.

"Hippolytus," Euripides. There's some really good Gender Studies-fodder in here, but I don't have it in me.

The Fortress of Solitude, Jonathan Lethem. I got around to picking up this one based on Lethem's excellent work on Marvel Comics' "Omega the Unknown." The message here is that comic books are a totally valid basis for forming literary tastes, and anyway, "Omega" is better than Fortress.

Melmoth the Wanderer, Charles Robert Maturin. This one I picked up because I really liked a comic book with a character named "Melmoth." Seriously. This turned out to be a horrible reason to pick up a 600+ page book. I never finished it, having gotten mired in "The Spaniard's Tale" a lengthy antimonastic screed wedged into this Gothic novel. Honestly, it might be a pretty good book if you just skip that one part.

Maps and Legends, Michael Chabon. I didn't pick up this one just because Chabon wrote a few essays about comics, nor because comic artist Jordan Crane designed the book's amazing jacket, nor even because I read most everything McSweeney's puts out. I also read it because Chabon was apparently fond of D'Aulaires' Book of Norse Myths as a child, and this speaks highly of him.

A Good Man is Hard to Find, Flannery O'Connor. Holy crap, how come no one ever told me how good Flannery O'Connor was?! All this time I was under the impression she was pretty much the literary equivalent of Dixie Carter, but damn!

Atmospheric Disturbances, Rivka Galchen. I read this at the beach. It still smells like sunblock. This book began a brief mini-fascination with Argentina.

Final Exam, Julio Cortazar. This book just about killed my mini-fascination with Argentina. I'd been hearing good things about Cortazar for a little while, and I am entirely prepared to accept that this may not have been the right book to start with. Pretty much a novel in which early 20th C Argentinians walk through the foggy streets of Buenos Aires, just talking & talking about art & literature, and the fog is the more interesting part of the book. If you read the Scylla & Charybdis ep. of Ulysses and thought, "hmm, needs more wank," this is the book for you. In all fairness, I will probably make a second attempt at Cortazar, one where I tackle a different book. Also Borges. This was the year I realized I really should read some Borges.

Saturday, October 25, 2008

Sunday, June 15, 2008

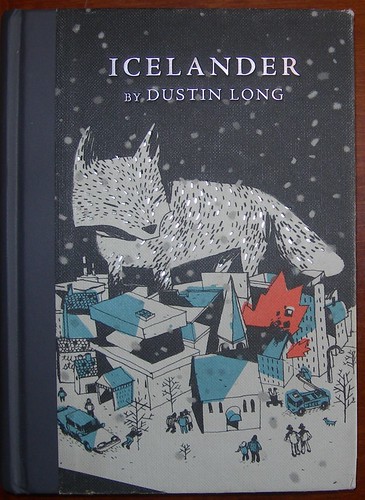

Icelander

by Dustin Long

249pp

3/16-4/12

This was a re-read, I guess intended to remind me what I most enjoy about McSweeney's Rectangulars. Back in 2006 when this book came out, I recommended it pretty heavily. It's damned enjoyable, and smart, too. Rereading it, I was pleased to find that it exceeded my recollection. I'd forgotten just how thematically rich the book is, especially to be such a fun book to read.

The book's "fun" comes largely from its setting in the world of Young Adult literature: "Our Heroine," as she's called throughout the book, grew up as the daughter of Emily Bean, who, with her family, solved forgery-related mysteries around the world, and whose adventures were the subject of a series of Young Adult novels with names like "The Greenland Gravestone Robberies." And the author of those books is modeled after Vladimir Nabokov. And the Nabokov-figure is revealed to have been the Bean Family's master-of-disguise archnemesis.

Also, there's a "lost" version of Hamlet, Norse mythology, an uncannily smart canine sidekick, footnotes, a society of subterranean Scandinavian ninjas, and a murder involving a house that doubles as a piece of experimental fiction.

So when I picked up the book a couple of years after my first reading it, remembering it for its zanier flourishes, I didn't expect much in the way of literary merit. I was surprised to rediscover a network of themes and associations holding it all together, such that all of the book's crazy parts are significant.

I heard a while ago that Dustin Long was working on something set in the 18th Century. I can't wait for that to come out.

249pp

3/16-4/12

This was a re-read, I guess intended to remind me what I most enjoy about McSweeney's Rectangulars. Back in 2006 when this book came out, I recommended it pretty heavily. It's damned enjoyable, and smart, too. Rereading it, I was pleased to find that it exceeded my recollection. I'd forgotten just how thematically rich the book is, especially to be such a fun book to read.

The book's "fun" comes largely from its setting in the world of Young Adult literature: "Our Heroine," as she's called throughout the book, grew up as the daughter of Emily Bean, who, with her family, solved forgery-related mysteries around the world, and whose adventures were the subject of a series of Young Adult novels with names like "The Greenland Gravestone Robberies." And the author of those books is modeled after Vladimir Nabokov. And the Nabokov-figure is revealed to have been the Bean Family's master-of-disguise archnemesis.

Also, there's a "lost" version of Hamlet, Norse mythology, an uncannily smart canine sidekick, footnotes, a society of subterranean Scandinavian ninjas, and a murder involving a house that doubles as a piece of experimental fiction.

So when I picked up the book a couple of years after my first reading it, remembering it for its zanier flourishes, I didn't expect much in the way of literary merit. I was surprised to rediscover a network of themes and associations holding it all together, such that all of the book's crazy parts are significant.

I heard a while ago that Dustin Long was working on something set in the 18th Century. I can't wait for that to come out.

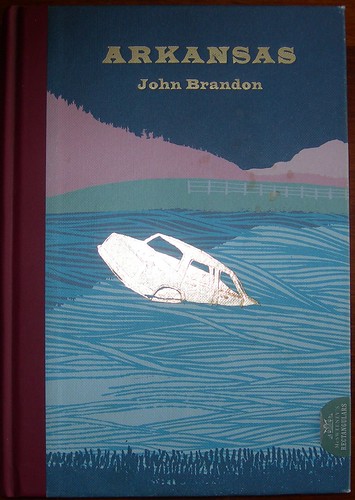

Arkansas

by John Brandon, 2008

230pp

03/02-03/15

So, I'm one of those people who reads the books of McSweeney's "Rectangulars" line as soon as they come out, even though I haven't really loved one since The Children's Hospital. And, man, I wanted to really like this book.

Call it "deep-fried pulp fiction," if you're fond of corny reductive labels. It follows a couple of sketchy characters into a colorful but logistically dunderheaded narcotics conspiracy spanning much of the Southeast. And that's what I thought I'd like about this book: being a resident of the Southeast with frequent interactions with the criminal element, I'd hoped to recognize the familiar in this book.

To be sure, Brandon gets a lot right, particularly in the "local color" department. Not that I'm familiar with Arkansas, where much of the book obviously is set, but I've lived my whole life in Southern flyover states, even in those state's own "flyover counties," far-removed from cities or even the Interstate. To the extent that they're thought about at all, these places exist as a mystery to educated, urban Americans, and the hipsters devoted to the output of a small San Francisco publishing house. "Here there be NASCAR fans." When I make a road trip across an unfamiliar stretch of interstate, I can't help but wonder about the lives of the people living off every exit. Very often I have this vague sense--"dread" is too strong a word--that the locals are seedy; I am suspicious of the people in these parts precisely because I've never seen fit to give them much thought, even though their territory stretches across most of the map. And Brandon captures the feel of life in these unconsidered places, where people work in factories making everyday objects whose fabrication you'd never once given a moment's thought.

I read this interview with Andrew Brandon shortly after finishing this book, and was disappointed I hadn't liked Arkansas more. I really want to like the book by the guy with nice things to say about Chattanooga, of all places.

But the biggest barrier to my enjoyment had to do with the treatment of petty and professional criminals. I'm a public defender in a small Southern town; I work with the folks who sling dope and carry guns around here. I didn't recognize Brandon's world, where colorful characters operate unwieldy criminal conspiracies that seem designed to maximize potential for betrayal or interdiction. But then, it's entirely possible that Brandon was being 100% faithful to the genre conventions of crime novels, if not to bleaker reality. Never having read a single word of Elmore Leonard or any of the rest, I really wouldn't recognize it. But it's likely I ought to hate the genre, not the writer.

You can't tell, but this is a signed copy. I picked it up at Atlanta's Criminal Records, which itself could be have made an appearance in this book (a flashback, maybe).

230pp

03/02-03/15

So, I'm one of those people who reads the books of McSweeney's "Rectangulars" line as soon as they come out, even though I haven't really loved one since The Children's Hospital. And, man, I wanted to really like this book.

Call it "deep-fried pulp fiction," if you're fond of corny reductive labels. It follows a couple of sketchy characters into a colorful but logistically dunderheaded narcotics conspiracy spanning much of the Southeast. And that's what I thought I'd like about this book: being a resident of the Southeast with frequent interactions with the criminal element, I'd hoped to recognize the familiar in this book.

To be sure, Brandon gets a lot right, particularly in the "local color" department. Not that I'm familiar with Arkansas, where much of the book obviously is set, but I've lived my whole life in Southern flyover states, even in those state's own "flyover counties," far-removed from cities or even the Interstate. To the extent that they're thought about at all, these places exist as a mystery to educated, urban Americans, and the hipsters devoted to the output of a small San Francisco publishing house. "Here there be NASCAR fans." When I make a road trip across an unfamiliar stretch of interstate, I can't help but wonder about the lives of the people living off every exit. Very often I have this vague sense--"dread" is too strong a word--that the locals are seedy; I am suspicious of the people in these parts precisely because I've never seen fit to give them much thought, even though their territory stretches across most of the map. And Brandon captures the feel of life in these unconsidered places, where people work in factories making everyday objects whose fabrication you'd never once given a moment's thought.

I read this interview with Andrew Brandon shortly after finishing this book, and was disappointed I hadn't liked Arkansas more. I really want to like the book by the guy with nice things to say about Chattanooga, of all places.

But the biggest barrier to my enjoyment had to do with the treatment of petty and professional criminals. I'm a public defender in a small Southern town; I work with the folks who sling dope and carry guns around here. I didn't recognize Brandon's world, where colorful characters operate unwieldy criminal conspiracies that seem designed to maximize potential for betrayal or interdiction. But then, it's entirely possible that Brandon was being 100% faithful to the genre conventions of crime novels, if not to bleaker reality. Never having read a single word of Elmore Leonard or any of the rest, I really wouldn't recognize it. But it's likely I ought to hate the genre, not the writer.

You can't tell, but this is a signed copy. I picked it up at Atlanta's Criminal Records, which itself could be have made an appearance in this book (a flashback, maybe).

Tuesday, June 3, 2008

Cosmicomics

by Italo Calvino, 1965

153pp

2/11 - 3/02

Calvino's always good for a change of pace. I've only ever really loved one of his books, If on a winter's night a traveler..., but I expect to continue gradually working my way through his body of work, one wild experiment at a time. I seem to be averaging one per year.

This is a collection of short stories, each narrated by "Qfwfq," who transmigrates across a number of forms--well, sometimes explicitly lacking "form"--over the aeons. It's sort of like a set of fables concerned with equations, simple lifeforms, and points in space, instead of barnyard animals.

Qwfwq and his similarly unpronounceable fellow-characters behave in pretty much human ways. Thus we have xenophobia among dinosaurs, jealousy among dense patches of stellar dust, and love among sightless molluscs. It's simultaneously an exploration of our tendency to invest the inanimate with human attributes--seeing a grinning mouth in the grill of a car--and an exercise in storytelling from a radically unfamiliar perspective. I was a little reminded of some old Asimov story about two-dimensional amoebic forms.

I have previously commented on the Harcourt Brace line of Calvino books, with their rather straightforward illustrations for the cover. This one is no exception, taking for its subject the book's first story, which was more of a fairy tale and didn't quite fit with the rest. You can't tell from the front, but the spines of these books all have this uniform band of colors, so that lined up on your shelves they look like a tasteful rainbow, or an array of paintswatches. My three other Calvino's just happen to be different shades of aubergine--conveniently enough for a guy who painted his shelves purple for no good reason--but this one's a brownish-goldenrod that ruins the scheme I had going.

153pp

2/11 - 3/02

Calvino's always good for a change of pace. I've only ever really loved one of his books, If on a winter's night a traveler..., but I expect to continue gradually working my way through his body of work, one wild experiment at a time. I seem to be averaging one per year.

This is a collection of short stories, each narrated by "Qfwfq," who transmigrates across a number of forms--well, sometimes explicitly lacking "form"--over the aeons. It's sort of like a set of fables concerned with equations, simple lifeforms, and points in space, instead of barnyard animals.

Qwfwq and his similarly unpronounceable fellow-characters behave in pretty much human ways. Thus we have xenophobia among dinosaurs, jealousy among dense patches of stellar dust, and love among sightless molluscs. It's simultaneously an exploration of our tendency to invest the inanimate with human attributes--seeing a grinning mouth in the grill of a car--and an exercise in storytelling from a radically unfamiliar perspective. I was a little reminded of some old Asimov story about two-dimensional amoebic forms.

I have previously commented on the Harcourt Brace line of Calvino books, with their rather straightforward illustrations for the cover. This one is no exception, taking for its subject the book's first story, which was more of a fairy tale and didn't quite fit with the rest. You can't tell from the front, but the spines of these books all have this uniform band of colors, so that lined up on your shelves they look like a tasteful rainbow, or an array of paintswatches. My three other Calvino's just happen to be different shades of aubergine--conveniently enough for a guy who painted his shelves purple for no good reason--but this one's a brownish-goldenrod that ruins the scheme I had going.

Monday, June 2, 2008

Gang Leader for a Day

by Sudhir Venkatesh, 2008

302pp

01/27/08-02/02/08

Careful readers of this blog will note a one month gap in the reading dates between this book and the book previous. Of course, I wrote that last blog post, oh, about 3 months ago. I can't really account for either lacuna. I remember there being a time where other, less demanding forms of narrative dominated my attention. I believe "The Wire" was on the air at the time. This of course can only partially account for my apparent sabbatical from reading, just as the stresses of work & turtle-ownership, and the intimidation inspired by a growing pile of unblogged, read books can only partly explain my three month silence on teh blogz.

So I guess I'm saying that the next few entries will be rough sketches of Book Reports. The books are already fading in my memory. The witty comments that occurred to me while reading are long gone.

I want to say I picked up this book the week it came out, and grew steadily more irked as its hype expanded across my personal NPR/NYT/elitist bubble. One would rather avoid the conclusion that one buys the same books as one's insufferable peers. I suppose I got what I deserved; this book was essentially spun out of the talked-to-death Freakonomics.

So you're likely familiar with the schtick: "A rogue sociologist takes to the streets," as the dust jacket says. Venkatesh, as a PhD student, ingratiates himself into the world of Chicago's notorious Robert Taylor housing projects. Apparently he studied "the underground economy," and it might be interesting to see some of his more academic writing on that subject. This book, however, is mostly an exercise in shock & voyeurism. Which is not especially groundbreaking; there's a reason we call it "slumming." Still though, the book packs quite a vicarious thrill, and it's fascinating to see the many ways the gangs functioned as quasi-community organizations. It can be eye-opening in the same way as "The Wire."

Venkatesh has apparently managed to parlay his degree (& Richard Roundtree's jacket) into a brisk gig as an authority on the Street. So far, he's been tapped to weigh in on such "hood" topics as The Wire, Grand Theft Auto, Spitzer's call girl, and Barack Obama.

302pp

01/27/08-02/02/08

Careful readers of this blog will note a one month gap in the reading dates between this book and the book previous. Of course, I wrote that last blog post, oh, about 3 months ago. I can't really account for either lacuna. I remember there being a time where other, less demanding forms of narrative dominated my attention. I believe "The Wire" was on the air at the time. This of course can only partially account for my apparent sabbatical from reading, just as the stresses of work & turtle-ownership, and the intimidation inspired by a growing pile of unblogged, read books can only partly explain my three month silence on teh blogz.

So I guess I'm saying that the next few entries will be rough sketches of Book Reports. The books are already fading in my memory. The witty comments that occurred to me while reading are long gone.

I want to say I picked up this book the week it came out, and grew steadily more irked as its hype expanded across my personal NPR/NYT/elitist bubble. One would rather avoid the conclusion that one buys the same books as one's insufferable peers. I suppose I got what I deserved; this book was essentially spun out of the talked-to-death Freakonomics.

So you're likely familiar with the schtick: "A rogue sociologist takes to the streets," as the dust jacket says. Venkatesh, as a PhD student, ingratiates himself into the world of Chicago's notorious Robert Taylor housing projects. Apparently he studied "the underground economy," and it might be interesting to see some of his more academic writing on that subject. This book, however, is mostly an exercise in shock & voyeurism. Which is not especially groundbreaking; there's a reason we call it "slumming." Still though, the book packs quite a vicarious thrill, and it's fascinating to see the many ways the gangs functioned as quasi-community organizations. It can be eye-opening in the same way as "The Wire."

Venkatesh has apparently managed to parlay his degree (& Richard Roundtree's jacket) into a brisk gig as an authority on the Street. So far, he's been tapped to weigh in on such "hood" topics as The Wire, Grand Theft Auto, Spitzer's call girl, and Barack Obama.

Saturday, March 8, 2008

At Swim-Two-Birds

by Flann O'Brien, 1951

239pp

12/22/07-12/31/07

For those of you keeping score, this is the third Flann O'Brien book I read in 2007. I never set out to do so. I don't pretend to 100% understand this phenomenon, which is fitting, because I don't pretend to 100% understand O'Brien.

I have this peculiar love of frame stories & metafiction. I can't justify it--really, I half-want to dismiss the stuff as gimmick & wankery--but it somehow thrills me to read a real head-trip of a book. Of course this was just such a book, one that might be easier to summarize with diagrams than with words. The outer frame follows an Irish student, more inclined toward drink & sleep than studies, who writes a book. In that book, a moralizing old man writes a book that draws on a variety of styles & characters: Celtic myth, medieval poem, and the improbable cowpunchers of Dublin. This "inner" author forces his characters to live with him, under his roof, until they conspire to hijack the narrative against him. Disparate literary styles are mimicked & mashed-up to comic effect, and with virtuoso skill.

For years the frequent mention of Joyce when discussing O'Brien mystified me. Over the past year this has made more & more sense.

A little after I read the book, this piece was posted on Slate, for some reason. It was really pleasing to read: I love to picture Nathaniel Rich saying "Y'know what? Flann O'Brien could fucking write," to which a cigar-chomping, green-visored editor must've replied, "Print it, my boy!" I of course anticipated Rich's comparison between O'Brien & Sterne, but it probably was never that original a sentiment to begin with.

This was also the third book from Dalkey Archive Press (Normal, IL) that I read in 2007. Whatever it says about me that I read three O'Brien books in '07, reading three Dalkey Archive books (The Dalkey Archive being one of them) probably says roughly the same thing.

"The Dalek Archive" popped into my head just now, which idea tickles the hell out of me. If you are similarly amused, you can rest assured that you're alright in my book.

239pp

12/22/07-12/31/07

For those of you keeping score, this is the third Flann O'Brien book I read in 2007. I never set out to do so. I don't pretend to 100% understand this phenomenon, which is fitting, because I don't pretend to 100% understand O'Brien.

I have this peculiar love of frame stories & metafiction. I can't justify it--really, I half-want to dismiss the stuff as gimmick & wankery--but it somehow thrills me to read a real head-trip of a book. Of course this was just such a book, one that might be easier to summarize with diagrams than with words. The outer frame follows an Irish student, more inclined toward drink & sleep than studies, who writes a book. In that book, a moralizing old man writes a book that draws on a variety of styles & characters: Celtic myth, medieval poem, and the improbable cowpunchers of Dublin. This "inner" author forces his characters to live with him, under his roof, until they conspire to hijack the narrative against him. Disparate literary styles are mimicked & mashed-up to comic effect, and with virtuoso skill.

For years the frequent mention of Joyce when discussing O'Brien mystified me. Over the past year this has made more & more sense.

A little after I read the book, this piece was posted on Slate, for some reason. It was really pleasing to read: I love to picture Nathaniel Rich saying "Y'know what? Flann O'Brien could fucking write," to which a cigar-chomping, green-visored editor must've replied, "Print it, my boy!" I of course anticipated Rich's comparison between O'Brien & Sterne, but it probably was never that original a sentiment to begin with.

This was also the third book from Dalkey Archive Press (Normal, IL) that I read in 2007. Whatever it says about me that I read three O'Brien books in '07, reading three Dalkey Archive books (The Dalkey Archive being one of them) probably says roughly the same thing.

"The Dalek Archive" popped into my head just now, which idea tickles the hell out of me. If you are similarly amused, you can rest assured that you're alright in my book.

Tuesday, March 4, 2008

amulet

by Roberto Bolaño, 1999

184pp

12/14/07-12/22/07

I'd probably never regret the act of reading, were it not for the certainty that there are so damned many good books out there I'd like to read. Every week the New York Times, Fresh Air, and the front table at Borders bring ten or twenty noteworthy new books to my attention; of these, a good three or four sound worth reading, at least until I forget about them, or they're revealed as massive hoaxes. So when I try out a book and don't like it, I'm keenly aware of the book I could've been reading.

I was taken in by some year-end hype when I picked up this book. Bolaño's The Savage Detectives appeared on NYT's "Top 10 Novels of 2007" list. That book was made to sound interesting, but its length made it a dodgy proposition. I decided to sample some of Bolaño's shorter writing.

Also of some relevance when I picked up this book: I've particularly enjoyed a few Hispanic/Latin American creators the past year or so: the Hernandez brothers, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Salvador Plascencia, even Gabriel Garcia Marquez, to a certain extent. I figured I was on some kind of kick, and thought I'd follow through with "[h]is generation's premier Latin-American writer."

To be sure, maybe I would've appreciated this book if I actually knew a thing or two about Latin American writers of any generation. This is the first-person account of the toothless, Uruguayan "Mother of Mexican Poetry." Though she writes no poetry herself, she cavorts with the artists and Bohemians of Mexico City in the late 60s. Kind of like A Moveable Feast, only the Mexican version. Despite my recent interest, I am entirely ignorant of Mexican writers (or Latin American, for that matter), so I'm unclear as to whether the writers & artists the narrator spends her time with are fictitious, or actual pillars of a genuine Mexican literary scene. I could quickly consult Wikipedia to clear this up, but am for some reason disinclined.

Further proof of my ignorance: this book largely centers around the apparently notorious political unrest of Mexico City, 1968. Eurocentric that I am, I was rather more familiar with Paris's troubles of that year. Apparently the University of Mexico was invaded by the Army, and it seems that this event was seared into the consciousness of the Mexican people. What next, Mexican Situationists?

So, I'm thinking an art director designed a really good dust jacket for this book, but on her way down the hall to her boss's office, she bumped into an art director who happened to be working on some homoerotic bodice-ripper, papers flew from the portfolio of the one art director into the portfolio of the other art director, and amulet ended up with this gay-ass cover.

184pp

12/14/07-12/22/07

I'd probably never regret the act of reading, were it not for the certainty that there are so damned many good books out there I'd like to read. Every week the New York Times, Fresh Air, and the front table at Borders bring ten or twenty noteworthy new books to my attention; of these, a good three or four sound worth reading, at least until I forget about them, or they're revealed as massive hoaxes. So when I try out a book and don't like it, I'm keenly aware of the book I could've been reading.

I was taken in by some year-end hype when I picked up this book. Bolaño's The Savage Detectives appeared on NYT's "Top 10 Novels of 2007" list. That book was made to sound interesting, but its length made it a dodgy proposition. I decided to sample some of Bolaño's shorter writing.

Also of some relevance when I picked up this book: I've particularly enjoyed a few Hispanic/Latin American creators the past year or so: the Hernandez brothers, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Salvador Plascencia, even Gabriel Garcia Marquez, to a certain extent. I figured I was on some kind of kick, and thought I'd follow through with "[h]is generation's premier Latin-American writer."

To be sure, maybe I would've appreciated this book if I actually knew a thing or two about Latin American writers of any generation. This is the first-person account of the toothless, Uruguayan "Mother of Mexican Poetry." Though she writes no poetry herself, she cavorts with the artists and Bohemians of Mexico City in the late 60s. Kind of like A Moveable Feast, only the Mexican version. Despite my recent interest, I am entirely ignorant of Mexican writers (or Latin American, for that matter), so I'm unclear as to whether the writers & artists the narrator spends her time with are fictitious, or actual pillars of a genuine Mexican literary scene. I could quickly consult Wikipedia to clear this up, but am for some reason disinclined.

Further proof of my ignorance: this book largely centers around the apparently notorious political unrest of Mexico City, 1968. Eurocentric that I am, I was rather more familiar with Paris's troubles of that year. Apparently the University of Mexico was invaded by the Army, and it seems that this event was seared into the consciousness of the Mexican people. What next, Mexican Situationists?

So, I'm thinking an art director designed a really good dust jacket for this book, but on her way down the hall to her boss's office, she bumped into an art director who happened to be working on some homoerotic bodice-ripper, papers flew from the portfolio of the one art director into the portfolio of the other art director, and amulet ended up with this gay-ass cover.

Tuesday, February 19, 2008

Pnin

by Vladimir Nabokov

191pp

11/24/07-12/14/07

This is as good a place as any for an apology. I've gotten way behind in my blogging. I apologize to the internet, and to the housing market, for good measure.

Thus I really can't remember why exactly I picked up this book almost couple of months ago. I seem to recall there being some mention of Nabokov. And then he came up again in that godawful "Sex Children" piece in Best American Essays. So I guess I felt like finally getting around to reading Nabokov, if not at the most obvious starting point. My selection probably had something to do with its mention in this cute piece in Slate.

Is "academic satire" a genre? I suppose this is a sort of "campus novel", one that, like Lucky Jim, is more concerned with professors than coeds. Professor Timofey Pnin is a sweetly foreign professor at a small Eastern college a decade before campus unrest; a time when academia was an elbow-patched, cocktail-swilling, boys' club. Pnin seems socially inept, but it's more fair to say he's doubly out of place, in America & in its rarefied university atmosphere. Pnin's frequent confusion and mangled English are played for comic effect, or at least the kind of comic effect that ran in The New Yorker in the Fifties. That's really about all I remember about the book.

One memory of the act of reading it stands out, however: I had to wait several minutes on a cold MARTA platform, entertaining a three year-old until the train arrived. I'd not been prepared for this, and had only this paperback in my pocket. Anyhow, I must have kept her attention for twenty minutes with this book. The book's action couldn't have interested her--something about renting an apartment in a university town--but the words kept her attention, which struck me as a serious testament to Nabokov's craft. A creative writing workshop could probably do worse than require students to read their pieces to three year-olds.

This cover initially struck me as terribly bland & unimaginative, but while reading the book I realized the photo's practically a literal illustration, and may well have been staged for just this purpose. The image of a man and a squirrel on a path comes up two or three times, and I don't know that I would have noticed if not for the cover.

191pp

11/24/07-12/14/07

This is as good a place as any for an apology. I've gotten way behind in my blogging. I apologize to the internet, and to the housing market, for good measure.

Thus I really can't remember why exactly I picked up this book almost couple of months ago. I seem to recall there being some mention of Nabokov. And then he came up again in that godawful "Sex Children" piece in Best American Essays. So I guess I felt like finally getting around to reading Nabokov, if not at the most obvious starting point. My selection probably had something to do with its mention in this cute piece in Slate.

Is "academic satire" a genre? I suppose this is a sort of "campus novel", one that, like Lucky Jim, is more concerned with professors than coeds. Professor Timofey Pnin is a sweetly foreign professor at a small Eastern college a decade before campus unrest; a time when academia was an elbow-patched, cocktail-swilling, boys' club. Pnin seems socially inept, but it's more fair to say he's doubly out of place, in America & in its rarefied university atmosphere. Pnin's frequent confusion and mangled English are played for comic effect, or at least the kind of comic effect that ran in The New Yorker in the Fifties. That's really about all I remember about the book.

One memory of the act of reading it stands out, however: I had to wait several minutes on a cold MARTA platform, entertaining a three year-old until the train arrived. I'd not been prepared for this, and had only this paperback in my pocket. Anyhow, I must have kept her attention for twenty minutes with this book. The book's action couldn't have interested her--something about renting an apartment in a university town--but the words kept her attention, which struck me as a serious testament to Nabokov's craft. A creative writing workshop could probably do worse than require students to read their pieces to three year-olds.

This cover initially struck me as terribly bland & unimaginative, but while reading the book I realized the photo's practically a literal illustration, and may well have been staged for just this purpose. The image of a man and a squirrel on a path comes up two or three times, and I don't know that I would have noticed if not for the cover.

Tuesday, January 8, 2008

Four Trials

by John Edwards, 2004

236pp

Read 11/20 - 12/10

For his unconventional 2004 campaign book, John Edwards chose to write an experimental sequel to Kafka' The Trial, making him the first candidate since Nixon (Six Crises, The Public Burning) to win the support of both postmodernist and expressionist voting blocks.

Sigh. In my world, Edwards secured the '04 nomination, and went on to win the presidency.

This in no ways constitutes an endorsement on the part of this humble blog, but I really think a lot of people--people well outside his current base--would warm up to Edwards after reading this book. (It could similarly affect attitudes toward plaintiffs' attorneys). Which, yes, is the point of campaign lit. And no, I've never read a single other presidential campaign book. I pretty willfully avoid them, and as such I presume to know a thing or two about them. Thus I can tell you that this is not a typical campaign book. It doesn't set forth any bold visions for America, nor does it primarily concern itself with relating Edwards' biography. Granted, it's impossible to read this book without coming away with a sense of Edwards' thoughts on personal & social justice, and you ought to be able to pass a quiz on his background and family. But the book cleverly embeds the electioneering inside a collection of compelling courtroom dramas. The real-life story arcs here are amazing, as is Edwards' finesse. Having taken trial practice classes in a North Carolina law school, I'd pretty well had it drilled into my head that Edwards is technically brilliant, but the book gives the reader some idea how superhumanly dedicated and hardworking that kind of lawyer has to be.

There is a single point, though, where Edwards' credibility falters: waiting on a jury verdict, he advises his client to reject a large settlement offer because it was less than his client "deserved." Bullshit. Edwards is a calculating professional, and he rejected the offer based solely on the probability of a higher award from the jury. Haughtily snubbing the offer out of abstract concerns for what his client "deserved" was never an option.

Borrowed book! I borrowed a book! Terrible human being that I am, I read this despite having at least two other borrowed books in the queue whose indulgent owners are probably running out of patience.

236pp

Read 11/20 - 12/10

For his unconventional 2004 campaign book, John Edwards chose to write an experimental sequel to Kafka' The Trial, making him the first candidate since Nixon (Six Crises, The Public Burning) to win the support of both postmodernist and expressionist voting blocks.

Sigh. In my world, Edwards secured the '04 nomination, and went on to win the presidency.

This in no ways constitutes an endorsement on the part of this humble blog, but I really think a lot of people--people well outside his current base--would warm up to Edwards after reading this book. (It could similarly affect attitudes toward plaintiffs' attorneys). Which, yes, is the point of campaign lit. And no, I've never read a single other presidential campaign book. I pretty willfully avoid them, and as such I presume to know a thing or two about them. Thus I can tell you that this is not a typical campaign book. It doesn't set forth any bold visions for America, nor does it primarily concern itself with relating Edwards' biography. Granted, it's impossible to read this book without coming away with a sense of Edwards' thoughts on personal & social justice, and you ought to be able to pass a quiz on his background and family. But the book cleverly embeds the electioneering inside a collection of compelling courtroom dramas. The real-life story arcs here are amazing, as is Edwards' finesse. Having taken trial practice classes in a North Carolina law school, I'd pretty well had it drilled into my head that Edwards is technically brilliant, but the book gives the reader some idea how superhumanly dedicated and hardworking that kind of lawyer has to be.

There is a single point, though, where Edwards' credibility falters: waiting on a jury verdict, he advises his client to reject a large settlement offer because it was less than his client "deserved." Bullshit. Edwards is a calculating professional, and he rejected the offer based solely on the probability of a higher award from the jury. Haughtily snubbing the offer out of abstract concerns for what his client "deserved" was never an option.

Borrowed book! I borrowed a book! Terrible human being that I am, I read this despite having at least two other borrowed books in the queue whose indulgent owners are probably running out of patience.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)