448pp / 526 pp

08/18/07 - 09/09/07

After reading a couple of books that weren't quite what comes to mind when people ask "So, what kind of books do you like to read?" I read this book, which I'd been meaning to read for some time.

This is one of those books that seems to often come up in discussions of other books and authors I like; if I encounter a book often enough in such contexts, I'm likely to read it. Plus the description "the post-modern novel before there was anything to be modern about" seems engineered to pique my interest.

You might recognize that quote from the 2005 movie, Tristram Shandy: A Cock & Bull Story. And here's the thing: though I realize that the better sort of readers are loathe to discuss a good book in terms of its movie adaptation, while reading this book my thoughts kept turning to the film. Specifically, although the movie purports to fail in adapting the book to the screen (instead focusing on the actors themselves), I kept marveling at how well the filmmakers translated the book to film.

When I first saw the movie, before reading the book, I was disappointed that only the first twenty minutes or so were spent depicting Tristram Shandy's plot. But then, the plot hardly happens in the book, either. Tristram Shandy sets out to tell the story of his own life, starting at conception, but due to a series of digressions and interruptions, he barely manages to tell the story of his birth. He's the most dilatory narrator since Scheherazade, if unintentionally so.

So instead of the story of an English gentleman which a reader might expect, we are instead subjected to his inane opinions, his father's preposterous theories (which remind me of DeSelby from The Third Policeman; a mini Irish Lit course focusing on Sterne, Joyce, and O'Brien would be fun), his Uncle Toby's military obsession, and a number of abortive frame stories. Again, the movie does a remarkable job of similarly frustrating the viewer's expectations.

I was surprised by the extent to which I found this book to be plainly funny. I don't expect the formal tone of an eighteenth century novel to make me laugh out loud, but this book managed to, several times.

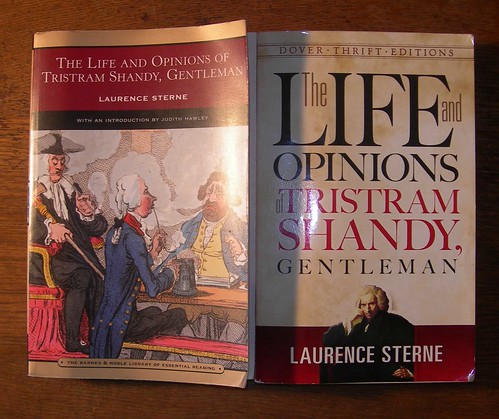

This is probably a strong recommendation of this book: a couple of days after starting it, I had to go to a small town where I knew no one, and would most likely be killing a few evening hours hanging around my hotel room. After leaving my house, I realized that I'd left the book behind. Whereas someone who wasn't thoroughly enjoying the book he's reading might have elected to pick up a magazine, or start a new book, or hope that there was something good on TV, I instead opted to pick up a backup copy.

This plan risked disappointment. I'd had to go to three different chain bookstores before finding my first copy, and I didn't have time to shop around before leaving town. I was near the East Cobb Borders, though, which actually had three different editions of the book. (This may become my quick test of the merits of a bookstore, and by extension, the local population: how many copies of Tristram Shandy do they carry?) What's more, one of them was the Dover Thrift Edition, retailing for an even $5. Granted, Dover's sub-par printing materials don't work so well in longer books (it was a little like reading a dried-out phonebook), but I respect Dover's mission of bringing the public domain affordably into the hands of the people, and in some ways the Dover version was superior to the Barnes & Noble Essential Reading version. Having compared a few different editions, I'll say that some English Department denizen somewhere would do well to edit an Annotated Tristram Shandy.

Of course, after finally getting to my hotel room, I realized that I had internet access and the damn thing's freely available online.