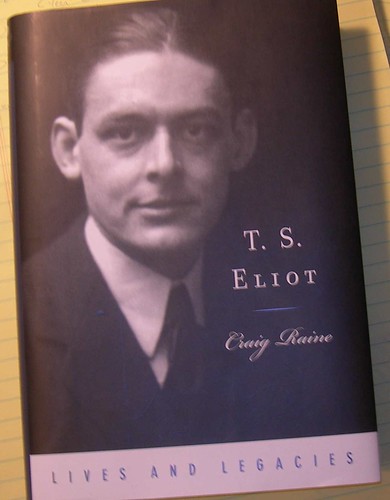

T.S. Eliot

by Craig Raine, 2006

202pp

Read: 1/19/07-1/28/07

I should start with the premise that T.S. Eliot is my absolute fave poet, ever. Perhaps I should've started with the premise that I am the kind of person to even have an absolute fave poet, ever, in this day and age.

In hindsight, I have absolutely no idea why I, at the age of 18, chose to do my AP English poetry presentation on Eliot. Nor can I recall the details of that project; I believe there was a clumsy analysis of "The Hippopotamus" and a surface-scratching ten page paper on The Wasteland. I didn't "get" the poetry then--either in sound or meaning--but I for some reason continued to adore the work of T.S. Eliot. I have no idea why. Over the next few years I read more Eliot, pretty much all of it. I wore out my cassettes with Ted Hughes reading Four Quartets--at one point broadcasting this and other poems over WREK for two hours. I read Joyce, and there got a whiff of the kind of serious literary analysis I'd need to conduct. I occasionally picked up, and put down, The Golden Bough. At one misguided point, I bloodied (my own) and tore my copy of The Wasteland: Facsimile and Transcript. A few weeks ago I was reading Selected Poems in the bathtub--it's something I do--when I was bitten by the Eliot bug all over again.

Fortuitously: I shortly thereafter read a glowing NYT review of this book, and pretty much immediately set out to buy it. I should probably tell you that I loved this book. But then, it may well be that I love reading all things Eliot.

This is not a good "first" Eliot book, if you're considering getting such a book for a young person in your life. Raine assumes you're familiar with Eliot's ouevre without bothering to catch you up to speed. When discussing particular poems, if you haven't committed them to memory, you ought to have Selected Poems at hand; Complete Poems and Plays would be handier; The Inventions of the March Hare comes into play at one point.

Not only does Raine assume his reader has already read Eliot, he assumes you've already read a bit *about* Eliot. He refers to, without really summarizing, criticisms of Eliot. He comments on poems that the average reader likely couldn't comprehend without reading someone's take on them.

But what Raine *does* have to say is pretty good. He looks out how two larger themes are explored throughout Eliot's work--one is reminded of the Joycean notion of artistic obsession--to wit: (1) "the buried life," a term Raine uses to mean both the passionate, artistic, adventurous lives most people avoid through hesitation; as well as the hidden emotions we each experience but cannot articulate or even really know; and (2) Eliot's "anti-Romantic" tendency, a rejection of bombastic emotion in poetry, in favor of an exploration of equally universal, if less artistically-explored, emotions. And he does a pretty good job of finding these themes in a variety of Eliot's poems; this approach succeeds with Eliot's shorter works, less so with the lengthier examinations of The Wasteland and Four Quartets. In fact, I'd go so far as to say that if you read the first two chapters--concerned with 12 or so shorter poems--you wouldn't be at too great a loss if you skipped the chapters on the longer poems, or the plays, or the criticism.

The book avoids biography as much as possible. Raine dismisses as unfounded speculation about Eliot's marriage, sexuality, attitudes toward Judaism, etc. as unfounded, and where there's genuine ambiguity Raine begins with the proposition that Eliot could do no wrong (which much endeared him to me).

Hey, remember seventh grade Language Arts? How before beginning a novel, your teacher would assign a vocab list drawn from words found in that novel with uncommon frequency? Should you read this book, you might find yourself looking up:

- topos

- bathos

- lexis

- zeugma

- expatiate

This book is part of Oxford University Press's "Lives and Legacies" series. Generally, I'm pretty leery about these series where a publisher decides "great writers writing about great writers (or thinkers) = $$$$$!!!" (other encounters with this format include David Foster Wallace writing about Cantor for Atlas/Norton's joint "Great Discoveries series;" William T. Vollman writing about Copernicus for same series; and Robert Pinksy writing about David for Shocken's "Jewish Encounters." Results vary.) The dust jacket to this book seems to sum up the compromises & limitations inherent to such series: "Brief, erudite, and inviting..." This book, at least, was too short to go into any serious academic discussion, but it was nevertheless written for a sophisticated audience (it's put out by the people who publish the OED, after all). The format does succeed, however, inasmuch as Raine's perspective as a poet do give him some pretty neat insights as to language, and he has a great command of the stable of authors one has to discuss when discussing Eliot.

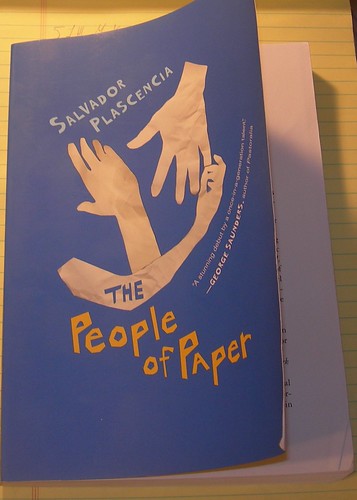

The People of Paper

by Salvador Plascencia, 2005

245pp

Read: 1/11/07 - 1/19/07

Perhaps the most typographically unique book I've ever read. (If you are inclined to check out this book on the basis of the foregoing sentence alone, congratulations: we'd probably make great pals. The bad news is you've chosen a hopeless life of form over content, and are doomed to pursue an increasingly empty series of "experiments" in style, and will probably die without ever knowing true love, or any sentiment for that matter. I blame late 20th Cent society, myself.) Not that the font is at all unusual--it seems to be the same as any McSweeney's book I've ever read (Garamond Three)--but the layout of the text is stylized. The book's chapters fall into three basic types (which the table of contents quasi-helpfully designates through a system of dots and dashes): those which follow a single character's first person narration, and which are laid out in a completely traditional manner; those which alternate among the third person narration of three given characters, again with traditional text arrangement; and those which follow any number of characters.

This last type of chapter is easily identified if you happened to flip through the book: on the verso you will see one wide column under the label "SATURN," this tells the action through an omniscient narrator. Essentially. On the recto, you see two narrow columns. The left column is labeled "LITTLE MERCED" and tells the action through the first person narration of the character of that name. The right column is reserved for first person narration from any one of the book's other characters; even unnamed, seemingly background characters are given voice.

Having laid out the book's ground rules, Plascencia of course breaks them by the novel's end. In the last chapter as many as six columns (or stubs of columns) crowd the page, and they are sometimes oriented perpendicular to the page (ie, sentences run bottom-to-top). I think this last gimmick is meant to resemble troops in battle formations.

There are other, less egregious devices employed: multiple dedication & title pages; words that seem to be scratched out & whole passages obscured by large black blobs (which themselves reflect a theme of occlusion, which is also part of the story); and **SPOILER ALERT** page 139, which contains only a single italicized word, "cunt".

But before the author can even play these stylistic games, there's the pesky task of coming up with a plot, right? The story here is such that I actually found myself wishing that Plascencia'd just delivered up a "straight" narrative about these people & their lives, without all the pomo hoo-ha. (I find myself wishing that about a lot of books.) People of Paper concerns a community of Mexican immigrants united by a benign street gang and a bizarre quasi-Catholic brand of mysticism (E.g., "When a saint dies, the smell of popourri extends out to a five-mile radius."). Also, there are mechanical tortoises. Federico de la Fe, the disconsolate father of Little Merced, convinces the local flower pickers and cholos to make war on Saturn, which he claims is a tyrant and voyeur, and the reason his wife left him. The gang's "war" involves efforts to hide their lives and inner thoughts from the ringed planet. And then the metafiction kicks in.

And just as the tricks played with form are justified by their relationship with the text's content, Plascencia's metafictional acrobatics are redeemed by virtue of their raw emotional content. The author's own emotional frustrations propel the book's creation. There's actually a surprising amount of sentiment for such willfully experimental fiction. Sadness, and escaping it through futile & unhealthy means is ultimately one of the book's major themes.

Speaking of themes, I feel like I would maybe benefit from a methodical re-read. The book is rife with images and themes that scream for cataloguing and cross-indexing. If I were teaching this book to a bunch of high schoolers, I'd create a worksheet, a kind of literary device matrix. The rows would be named for the various characters, and across the top would be "honeybees," "blood," "foreskin," "flowers," "paper," "Napoleon," "lime," "Oaxacan songbirds," "self-mutilation," "cold climates," "celebrity," "colonialism," etc. Bright young kids could make note of what character encounters what theme/image on what page, maybe copying the relevant sentence, and there you'd have the book's scheme.

This was originally published as part of McSweeney's "Rectangular" series, before I began to read those books as soon as they come out. Purchasing this at Borders, I had a choice between the handsome hardback McSweeney's first edition, and the cheaper paperback edition recently put out by Harcourt. If you've ever witnessed me standing before the wall of yogurt at the grocery store, using a spiral-bound notebook to calculate exactly which brand costs least per ounce that particular week, you've probably guessed which edition I ended up buying. Oddly, this choice actually affects the body of the book: the author is at one point accused of selling his personal experiences for "fourteen dollars and the vanity of your name on the book cover." I suppose the text originally said "twenty-two ninety-five and the vanity..."

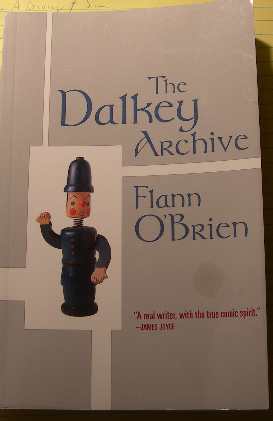

The Dalkey Archive

by Flann O'Brien, 1964

204pp

Read: 12/30/06-01/03/07

This is probably the only book I've read with a cover blurb from James Joyce. Not about Joyce, not likening O'Brien to Joyce (though there are plenty such blurbs, most notably from Anthony Burgess), but a genuine bit of Joyceana, a quote in which Joyce himself calls O'Brien "A real writer, with the true comic spirit."

I picked up this book because I enjoyed The Third Policeman. I first heard about O'Brien in a conversation (in Dublin, June 16, 2002) in which someone said he really didn't understand why O'Brien was so frequently compared to Joyce, outside of their both being Irish. Which came to be my own opinion after reading Third Policeman. Whereas Joyce is the height of modernism, O'Brien is most definitely post-modern. While, yes, Joyce's otherwise intellectually dense writing is tempered by a sense of humor, O'Brien seemed to be going for intellectual yucks. After reading Dalkey Archive, however, it is clear: O'Brien got down on his knees & begged to be mentioned in the same breath as Joyce.

It seems to me that, whatever other experiences formed O'Brien as a writer, a sincere worship of Joyce's works was one of them. (Which, for the record, was the only rational course of action for a young writer in Ireland in the first half of the twentieth century.) O'Brien went to the same college as Joyce, having forged an interview with John Joyce for his college application. And The Dalkey Archive, set a few years after Joyce's death, features him as one of its characters, to great comic effect if you yourself happen to be a fan.

And that's what this book mostly goes for: comic effect. There's a point early on in which St. Augustine talks theology, and while that part is funny, it's especially erudite, kind of like a postmodern The Temptation of St. Anthony. I wish that O'Brien, having established a device for introducing historical personages and having offbeat conversations with them, had continued to do so. But he pretty much goes on to recycle some material from Third Policeman (though he'd written that book a couple of years earlier, it wouldn't be published until after his death, a couple of years later), throws Joyce into the mix, makes a few jokes about the Jesuit Society, and calls it quits. Smart and entertaining and quick, in equal parts, but if you've never read any O'Brien you'll want to start with The Third Policeman.

The copy I read happened to be published by "Dalkey Archive Press," which seems to be what Illinois State University chose to name its publishing arm. For some reason. Reading this book had a feeling of in some way coming full circle. The Joyce character talks about going to the Parisian bookshop of Sylvia Beach. I first bought Third Policeman at Shakespeare & Co., though that copy is now probably in Pittsburgh, I think, where I have never been. A real shame, since it was an edition you can't get in the States.

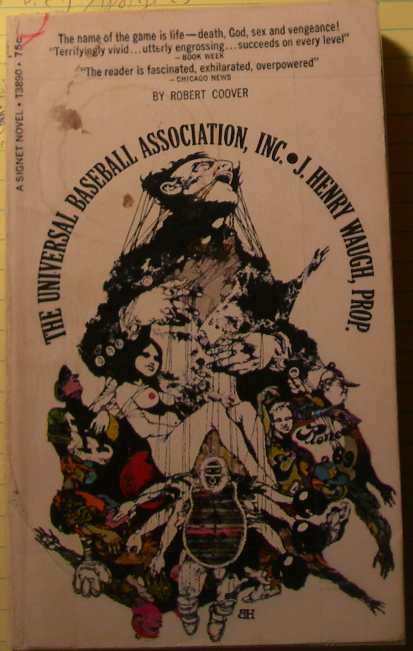

The Universal Baseball Association, Inc.; J. Henry Waugh, Prop.

Robert Coover, 1968

173pp

Read: 12/24/06 - 12/29/06

Know how you'll be reading a good book--typically this happens with the longer ones--and you're enjoying it, it really makes you think, etc., but when someone asks you what it's about, you're at an utter loss for a simple answer?

This book is the opposite. In an airtight, and surprisingly comprehensive nutshell: this book is about a middle-aged bachelor who escapes his otherwise tedious life by spending every free moment playing a dice-based baseball game of his own design. He keeps detailed statistics on a league full of imaginary players, and composes an elaborate league history. Having told you that, you've probably guessed about 80% of where this book goes: obsession, the human need to construct a narrative from a sequence of random events, the storyteller-as-God (I read somewhere that Waugh's name is supposed to be an expansion of the tetragrammaton, which if true is a nice touch), the creator's relationship to his creation.

Which whole thing made for a good premise for a short read, and anyway I was a few hundred miles from home and in need of reading material. I didn't develop any great expectations on the basis of this premise; mostly I was interested because I'd read The Public Burning a couple of years ago and was interested in getting another sampling of Coover's stuff. Even with tepid expectations, I was for the most part mildly underwhelmed. The premise was a little clever, and it was readable, and I was prepared for a book in which nothing much happens--that's sort of the point, innit?--but it nevertheless felt like the book's conflicts avoided their resolutions. The book's divided between Waugh's stagnant career & personal life, and the "action" in his imaginary baseball league. As a reader, I was never very invested in the players, and the ballplay dragged on. Come to think, that's arguably a testament to the book's fidelity to the game of baseball.

But then, in the end, a sort of a payoff. The last chapter is set in Waugh's "league," after the passage of one hundred seasons. Whereas the previous baseball action had been a celebration of nineteenth century baseball clubs and larger-than-life heroic players, the last chapter is peopled with their distant descendants, and the games have mutated into ceremonies in a religion based on the games of old. What's more, the previously un-showy narration has become a pitch-perfect (pundiferous!) imitation of Joycean wordplay and irreverence, complete with an Oliver St. John Gogarty figure. I was so pleasantly surprised by this last chapter that I'd probably say it was worth reading the entire preceding book (which was short, and not bad, mind you) just to get to this weird & unexpected finale.

I read a 1968 "Signet Novel" paperback, purchased for $1 at the bookstore at the back of the coffeeshop on College Ave in Ft. Collins, CO. I guess I'm sort of a fan of reading 1960s experimental fiction in the original paperback edition; for some reason it seems you can basically always find some Barth or Barthelme real cheap in any used bookstore, no matter where you are. I love reading an actual "literary" book that I can fit into my jeans' back pocket. Since these old paperbacks are usually on the verge of falling apart, I usually reinforce them by applying packaging tape to a book's spine & edges. This edition is notable for the naked woman who pops off its otherwise cluttered cover illustration. I assure you she is there out of strictly commercial consideration.