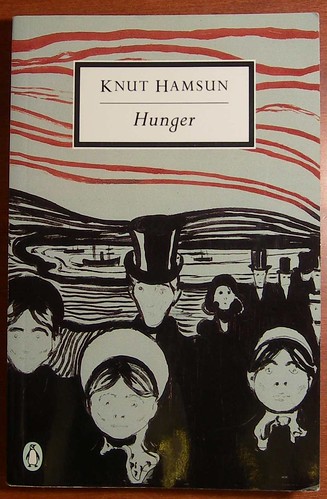

by Knut Hamsun, 1890

197pp

Sometimes a reader has to go out on a limb. I'd never heard of Knut Hamsun, but for some reason pulled this book off the shelves in the course of a peripatetic conversation with Ed at the East Cobb Borders. Partly my interest was piqued by the notion of a "Twentieth Century Classic" I'd not heard of, by a Nobel Prize-winning author I was likewise ignorant of. I confess, the back-cover puffery, invoking Dostoevsky, Camus, and Kafka, may have influenced me. But the most persuasive factor really may have been the cover: the Penguin Classics' title box (as smartly appropriated by Art Brut) set against a rather striking Munch.

Hey, are you wondering why exactly you've never heard of this book & author? For one thing, you'd be shocked how many Nobel Laureates for Literature you've never heard of. Indeed, looking at the first twenty years of the award, the only names which ring any bells (OK, aside from Maeterlinck) are those of a jingoist, a proselytizer, and, in the case of Mr. Hamsun himself, a Nazi sympathizer.

So, yeah. That's why you don't hear about him so much: Nazis tend not to get taught in our public schools.

Not to preoccupy myself with Hamsun's biography, but by all rights he ought to have been an Anarchist. In 1882, he came to the United States with nothing, gravitated to Chicago, where he was a streetcar conductor, stuffing his clothes with newspaper to keep warm against the wind. And so it's obvious: European immigrant, experiencing grinding poverty in Chicago at the time of the Haymarket Riot. This is how you constructed a would-be presidential assassin in the twilight of the nineteenth century. But history had different plans for him. In 1888, German freighter captain gave him free passage back to Norway, where, instead of the familiar Norwegian variety of grinding poverty he'd fled, Hamsun found literary success & national celebrity.

But so Hamsun was imminently qualified to write Hunger. The book is pretty much as its title suggests: it's the interior monologue of a desperately poor young man in the streets of Norway. The narrator fancies himself some kind of author but is met with little success in his efforts at composition or selling his work to newspaper editors. He goes days without food, and sleeps in cheap rented hovels, when he doesn't elect to sleep outdoors. He pawns his vest, he pawns the buttons from his coat for some meager food, only to leave himself that much more exposed to the cold winds.

If it were written today, Hunger would be an Oprah's Book Club selection. The narrator is never met with any Horatio Alger success, but he maintains his scruples. Whenever fate puts a few coins into his hands--which does in fact happen; the book has a comfortable rhythm, whereby the narrator begins in a state of desperation, grows worse, and after forty pages is met with an unexpected pittance--he feels honor-bound to buy an elderly man a meal, or practice anonymous charity, or to settle his account with his landlady. But what separates Hunger from "The Waltons" is that the narrator's scruples make him a fool. It is clear that he should put aside pride and seize opportunities, act in self-interest, escape the cycle of dereliction.

Sometimes the job of matching art to text must be very difficult, and surely the person who does that job over at Penguin must be a fascinating person, as she must be exceedingly well-read, and possessing a huge mental catalogue of art history. Presented with this book, however, she must have thought, "Brooding interior monologue? Desperation? Norwegian? Slap some Munch on that puppy," before taking an early lunch.