Euripides, 5th Cent. BC

about 20pp

A few years ago I was in the habit of reading Greek tragedies when I was "between" books. I read these during two different "breaks" from the same book.

I picked up "Alcestis," after Raine's book on Eliot described it as a "resurrection play" and the template for Eliot's "The Cocktail Party." The play is set in the aftermath of a neat little myth with which I wasn't familiar: Apollo, angry at Zeus for smiting his son Asclepius (poss. the awesomest figure in classical mythology), slays the Cyclopes (the Cyclopes being the ones who forge Zeus' lightning bolts). Zeus in retaliation forces Apollo to be a slave in a mortal's home. Which brings Apollo to the home of Thessalian king Admetus, where Apollo becomes the king's shepherd and is treated rather well. In gratitude, Apollo makes a deal with Destiny: Admetus can avoid his own death if he can get anyone else to substitute himself and die in his place.

Which brings us to the opening of the play. Admetus' friends and parents have refused to die in his behalf, and instead Alcestis, Admetus' wife and mother of his children, agrees to die. Apparently this is what a devoted Hellenic wife ought to do. And so she dies, and Admetus is distraught, and their kids are distraught. Enter Heracles, who's on his way to fetch some man-eating horses. Because Admetus would never dream of turning away Heracles, and because Heracles wouldn't stay chez Admetus if he knew that the master of the house was mourning his wife, Admetus conceals his house's state of mourning from Heracles. Naturally, Heracles finds out, and is so upset that he goes to Alcestis' tomb to wait for Death to come & claim her. So, off-stage, Death comes to the tomb, when Heracles beats up Death, thereby resurrecting Alcestis. Twenty five hundred years later, Superboy would punch a hole in reality.

It turns out that Euripides is Western Lit's go-to guy for the dramaticization of the life of Heracles. I'd always thought that he existed in outside of Classical Literature as handed down in epic poetry and drama; I figured we mostly knew the stories of Heracles through folklore, marble statues, and Kevin Sorbo. But Euripides wrote a few plays based on Heraclean myth, which one would have to think would pack the amphitheater way better than another damn play about Orestes.

Nor had I realized that Heracles had a full-fledged arch-nemesis in Eurystheus. The guy was a blood-relative to Heracles, and a rival for his power; it was Eurystheus who sent Heracles on his Labors. And when Heracles ascended into heaven, Eursytheus tried to wipe out his children. Which brings us to the "Heracleidae."

The sons of Heracles, under the charge of Iolaus--Heracles' own fidus Achates--have traveled from city-state to city-state seeking refuge. Every place they've gone has turned them away, swayed by Eurystheus' threat of Mycenaean force. Until the gang gets to Athens, naturally. The city must still be young, because it's under the rule of the two sons of Theseus. When reminded that they, like every Greek who could swing a club, are blood relatives of Heracles, they rebuke Eursytheus' herald and offer sanctuary to the Heraclids (dare I call them the HeraKids?). Of course the herald promises to return with Eurystheus' army, so Athens girds herself for war.

In accordance with the peculiarities of time in Greek drama, in the time it takes a servant or two to enter and exit, the Mycenaean army is outside Athens. And there's a problem. The oracle's been consulted, and she says Athens won't win unless the daughter of a noble is sacrificed. None of the nobles can bear to give up their own daughters, and no one wants to take a daughter by force. All is saved when Macaria, a virgin of suitable birth volunteers to be sacrificed, which makes her family proud. Apparently ancient Greece was rife with opportunities for the honorable act of feminine self-destruction.

So of course Athens wins, and the play really could end there, but it doesn't. Alcmene, Heracles' mom, demands the execution of Eurystheus. The chorus of Athenians politely explain that, as a captured prisoner, they don't have to kill him; to do so would go against their laws of war. To which Alcemene responds, in essence, "nuts to that!" They end up killing Eurystheus, and according to folklore, the presence of his corpse on Athenian soil protected the city from the descendants of Heracles, ie, Spartans & Argives.

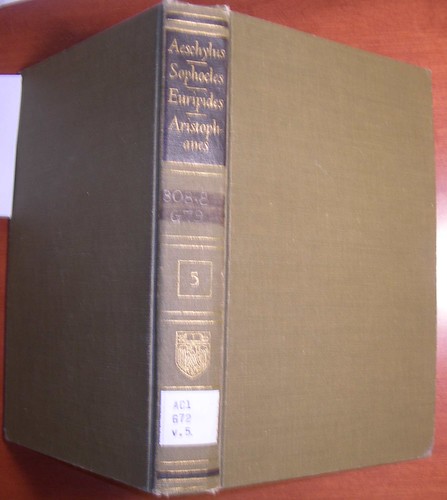

I got this book pretty cheap at the WFU Library book sale. It's a volume from the Encyclopaedia Britannica "Great Books of the Western World" series, and it's got about all the Greek drama you'd ever want. In its ~650 pages I'd guess it has about 50 plays. It does this by employing small type, arranged in two columns on every page, and by abbreviating characters' names in the stage instructions. Which just strikes me as such a beautifully low-tech means of storing and compressing data. In today's world of Google & wikiwhatnot, it's easy to forget just how impressive the notion of an encyclopedia used to be: the promise of substantially all of mankind's useful knowledge, leatherbound and right there on your bookshelves. The "Great Books" series was probably an extension of this same idea: fifty volumes or so gave you every word of every primary text of the Canon of Western Literature. As a sidenote, I bet encyclopedia salesmen were pretty cool. Not only were they drifters and drunks who couldn't hold down regular employment, their peculiar realm of salesmanship required them to be conspicuously erudite. I bet they had a strategy for entering your living room and proceeding to casually make reference to all the important things you don't know but feel you should.

No comments:

Post a Comment